#THISISEGYPT

SCULPTURE

Visiting the Pyramids, digital montage, from the collection of the Arab Image Foundation. Prototype for a VR (virtual reality) installation, 2016. © Lara Baladi.

"Egypt tourism campaign backfires after people tweet the real #ThisIsEgypt" reads the headline of the Independent on December 13th 2015.

This hashtag is still used today on social media to describe Egypt.

#ThisIsEgypt. Title is borrowed from Egypt's 2015 tourism campaign. Iron sculpture. 30 x 28 x 20 CM. Virtually There: Documentary Meets Virtual Reality, MIT. Photos by Sue Ding, Daniel Koff and Lara Baladi. © Lara Baladi.

This virtual reality mask is part of the project Vox Populi, Archiving a Revolution in the Digital Age. This wearable sculpture's form is inspired by a medieval scold that kept women from speaking.

In the timeline of the 2011 Egyptian revolution and it aftermath, this revisited torture apparatus, a contemporary viewmaster/VR mask marks the present period, i.e. the return of the military regime and the loss of freedom of speech.

This work was first shown during the MIT conference: Virtually There: Documentary Meets Virtual Reality organized by the Open Documentary Lab in Spring 2016.

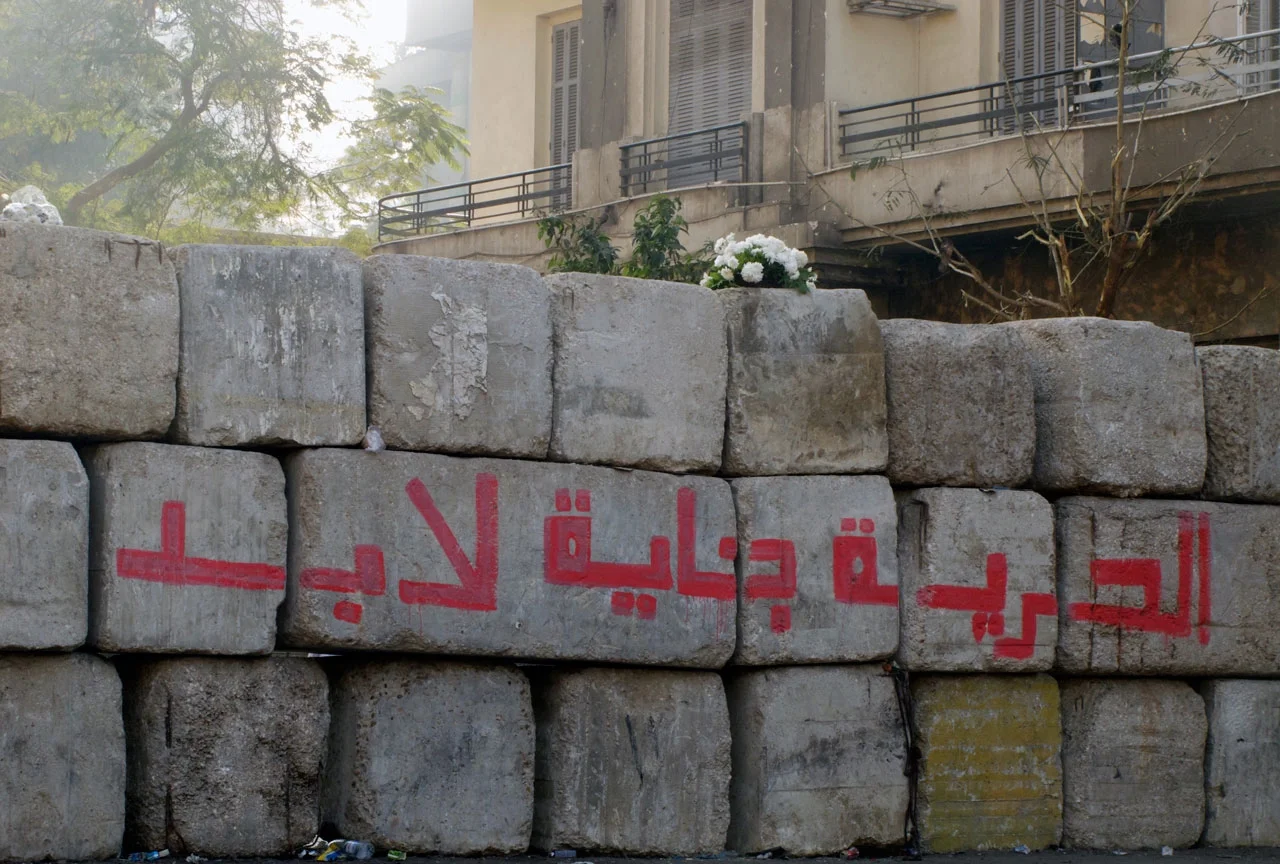

EL HOREYA GAYYA LABOD

SCULPTURE

Arabic, 'Freedom is Coming.' Title borrowed from a graffiti painted on a wall built by the Egyptian army in 2011 to stop revolutionaries from accessing the Ministry of Interior from Tahrir Square.

Iron (Officina Meccanica Ugo Farina, Egypt) and leather (Johnny Farah, Lebanon). 240 x 220 CM. Artwork commissioned by Marseille-Provence 2013. © Lara Baladi.

“… While I identify with being an Arab and with being a woman, I reject any definition of myself as a female Arab artist. It does no more than state the obvious in a way that reveals little or nothing. However, since the revolution, although I don't consider myself a feminist, my concerns about the barely hidden misogyny bubbling to the surface across the world have been amplified by the use of sexual abuse as a counter-revolution tool in Egypt, and by consequence my position in relation to women’s rights has changed. Expressions such as, “we are returning to the dark ages”, recur in everyday conversations in Cairo and on social networks. These fleeting statements reflect a deeper fear that we are returning to a time in which social hierarchies and systems of power are policed through sexual repression, harassment, and control. The policy of sexual repression that men live by consequence, creates a closed circle in which people descend into a spiral of mutual oppression.

Making of El Horeya Gayya Labod, Cairo, Egypt. © Lara Baladi 2013.

One could see my work El Horeya Gayya Labod (Freedom is Coming, 2013), comprising a larger than life-size (2.40 meter-high) chastity belt, as a straightforward response to the increasingly mediatised sexual repression and oppression of women promoted by reactionary religious movements particularly prevalent in the Middle East. If only it were that simple.

As a cultural tradition and device of sexual control, the chastity belt first appeared in ancient Egypt. The Pharaonic version was simply a string tied around a slave’s waist, signaling her sexual unavailability while also reinforcing her social status as inferior. Today, the chastity belt is commonly associated with European medieval culture. The brutal period from which it arises is a shocking reminder of how history is repeating it self. The rape and sexual abuse, of women and also of children and men, is used systematically to control dissent and defiance the world all over. In such an oppressive atmosphere, the need to erect a shield is obvious. The chastity belt becomes both an agent of and protection against such abuse.

A French seventeenth century chastity belt is the model for my leather and iron sculpture. As an artwork it addresses not only notions of freedom but also the question of boundaries. The title of the work is a direct reference to a piece of graffiti painted on one of the walls erected against the demonstrators by the Egyptian army in November 2011 following the Mohamed Mahmoud street clashes. The sculpture is large enough to engulf a human being, and in so doing becomes a cage. It is a prison made of iron, a substance that is obdurate and resistant to change, resonating with how people can become trapped by the historical circumstances of their era. What we’re experiencing now, especially in Egypt after the revolution, is a full-on counter-revolution and an extreme resistance to the possibility of an entirely new world. Liberals and secularists are becoming the minority, finding it necessary to hide and protect themselves. Ultimately, the belt represents this greater danger, this loss of freedom at large…”